Impars Project

Coordinator: Núria Garí

Interview

Text: Marcos Doespiritusanto

You recently held the exhibition Douleurs, Migraines et Sonates, and designed the official poster for the 79th Madrid Book Fair. How has the pandemic influenced your work over the past few months?

The emergence of a pandemic inevitably affects us all. Some projects have been cancelled, while others have had to adapt. Artistically, it has meant a radical evolution in the way I work. The current situation has taught me to listen to myself and overcome the fear of experimenting with new media.

Most of the production of Douleurs, Migraines et Sonates occurred during the lockdown. On a personal level, I noticed a very interesting change between the pre-pandemic pieces and the ones I did between March and May. It was a very hard few months, as my grandmother was hospitalised, my mother worked in the IFEMA field hospital and my father in a hospital in the Guadarrama mountains, while I was almost 400 km away from my family. I ended up mentally exhausted with an exhibition on the horizon. I saw work as a way out and the result was very different from anything I had produced before.

Douleurs, Migraines et Sonates seeks to take a condition such as migraines, which affects 15% of the world’s population, out of the personal sphere and reflect on the concept of pain. Why do you think today’s society sees pain and illness as taboo?

We are taught that suffering is weak, that pain makes us vulnerable and that it is a flaw. We forget that pain —both physical and emotional— can teach us a lot about ourselves, about how our body works; it makes us stronger.

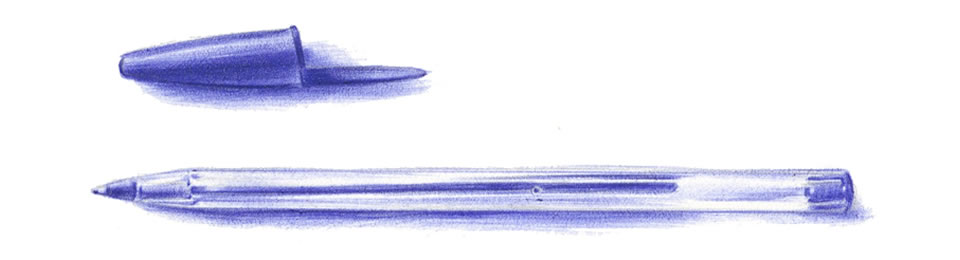

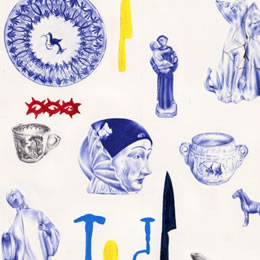

The exhibition features ceramics and drawings that combine BIC pen characteristic in your work and embroidery with acrylic and graphite. What value does each of these techniques bring to your creative universe?

The blue pen ended up being a differentiating feature in my work, it is a slow but very much appreciated tool. It has taken me several years to realise that the technique should not limit me, so I ended up using all the materials I like, as long as they add something to my work.

An example of this is the aura that accompanies a migraine, which causes vibrant coloured spots to appear in the field of vision. I couldn’t base an exhibition on migraines without adding those distinctive colours. I also made pieces from ceramic stoneware and drew objects from the same material to emphasise the concept of fragility.

Do you remember how your artistic vocation first came about and what led you to study Fine Art?

I’ve been drawing for as long as I can remember, so the vocation was always there.

From a very young age I remember my father painting whenever he had some free time, it felt very natural to me. I’ve been taking drawing classes since I was six years old. Whenever we would travel I always preferred visiting museums to amusement parks and if they asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would say that I wanted to study Fine Art. It is something I owe greatly to my parents and to my environment.

You inaugurated the exhibition La Memoria de las Piedras (The Memory of Stones) in 2019 at the Pepita Lumier gallery in Valencia. An exhibition that, in your words, is in memory of the mass graves, of those who disappeared during the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship. What inspired you to carry out this work at a time when democratic memory is once again at the centre of political debate?

I had been wanting to bring this project to fruition for a long time. The rise of far-right political parties made me stop and think about what we were doing wrong and I made the decision to act.

I found inspiration in my own family. My great-grandfather Andrés was one of many who disappeared and was buried in a mass grave during the Spanish Civil War, and my great-grandmother had to struggle to make sure her two children did not starve.

Talking about it over the years, I’ve come to realise that many families have a similar story and that, despite being recent history, new generations are very unaware of it. We try to bury the subject as deep as the bones of the hundreds of thousands of missing people, and by making it taboo, we run the risk of it being forgotten and eventually repeated.

About a year before, you drew some of the characters from the first act of Así que pasen cinco años, a play written by Federico García Lorca in 1931 that would end up becoming a dramatic premonition of his assassination in 1936. What was this project about?

It is part of the same exhibition as La Memoria de las Piedras, which includes pieces produced from late 2017 to early 2019. Federico García Lorca is one of the first names that comes to mind when we talk about people killed under Franco’s regime, and I felt that he had to feature in the exhibition no matter what.

I chose that particular play because, although it is not very well known, it is hypnotic, and its premonition motif is quite intriguing. It’s a real black legend. Así que pasen cinco años (Leyenda del Tiempo) was written in August 1931, and five years later, in August 1936, Federico was executed.

Besides, I have an almost mystical bond with this play. It has been popping up in my life in one form or another since I was sixteen, when a language and literature teacher first told me about it. In the near future, I would like start a personal project of illustrating the whole play as a way of coming full circle.

Two other vectors of your work are the role of women throughout history and an exploration of your own roots and genetic heritage. Where do these interests come from?

They grew very naturally. I have always been very interested in looking at the past as a basis for understanding the present. Ultimately what I do today is the result of what surrounds me and what I have learned. That’s why my greatest sources of inspiration end up being those closest to me, namely my grandmothers, my mother and the women of the family.

I have always felt that history has been told from a man’s perspective, eluding and belittling women. I can use drawing to make people think about this paradigm and form an opinion.

Designing Jorge Drexler’s album, Salvavidas de Hielo, in 2017 was a turning point in your career. How far have you come to start receiving requests of this kind? Do you see it as a matter of hard work or simply good luck?

In my experience, practice makes perfect, be consistent every day, keep a good portfolio and focus your work. Being active on social networks and having an up-to-date website means that you receive projects from all over the world. On the other hand, attending illustration fairs such as ILUSTRÍSIMA or desktop publishing fairs such as GRAF or TENDERETE has brought me closer to the publishing world, and made me realise who my audience was.

There is no denying that luck is also a factor. Some of my projects have come about because I was in the right place at the right time. Salvavidas de Hielo was one of them. Jorge Drexler came across a drawing of mine when he was looking for pencil portraits on the internet. If I hadn’t done those portraits years earlier, he would never have contacted me.

As an illustrator, you have worked for brands such as Diesel, Oysho and Calzedonia and publications such as El País Semanal, Cinemanía and Glamour. How do these types of commissions gel with your exhibitions and individual projects?

Some months everything runs very smoothly and others are more of a struggle. It is just as important for me to work for myself as it is for a client, everything is equal. So far, I have organised myself in such a way that I try to gather all the external requests in a few months, and then dedicate the rest of the year to personal work and artistic production. I always end up with an interesting project that interrupts my “ideal plan”, but I am grateful for it. I have found a balance between personal projects as an artist and work for clients as an illustrator.

What’s your view on the outlook for artists who, like you, are starting their professional careers? How do you think the cultural sector will fare following this current crisis?

The situation was already difficult before and in Spain, we don’t tend to prioritise culture. In spite of everything, the pandemic has led us towards a digitalisation of culture. If we can’t physically go to concerts, we buy tickets online and enjoy live streaming from our computers. This is gradually making our perception of culture more democratic, bringing it closer and making it more accessible.

I have personally experienced an increase in demand from individuals who want to order or acquire original work in small format, which is more affordable but just as valid. The truth is that it is encouraging, despite the context, to see new collectors emerging little by little.

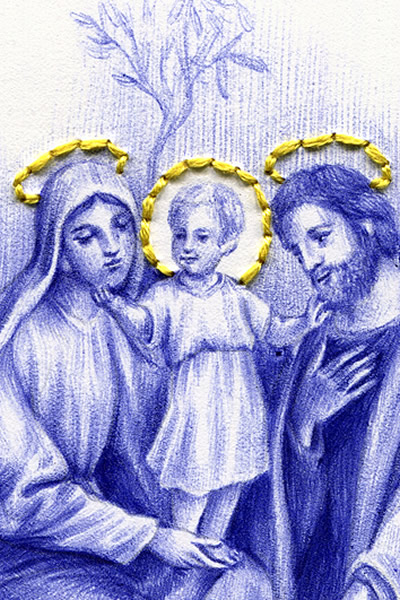

What is your design for the UIC Barcelona Christmas card based on? What does working for a university mean to you?

That was a very interesting project, a real challenge. It has made me reflect on how our perception of Christmas changes from childhood to adulthood. On how, in spite of everything, we are recovering old habits and the joy of celebrations.

I based my design on my childhood memories of Christmas in my parents’ village with the whole family. I thought about the rituals that are handed down from generation to generation, like putting up the nativity scene and the Christmas tree. That is why the card is called De herencias y tradiciones (Of Inheritance and Tradition).

If you had to define yourself as an artist in five words, what would you say?

Sensitive, patient, analogical, clairvoyant and determined (not to say stubborn).